“You have anorexia,” the clinician told me.

“I have ADHD, though,” I protested, as if both couldn’t be true.

She nodded in agreement. “You have anorexia and ADHD,” she affirmed. “And you need help.”

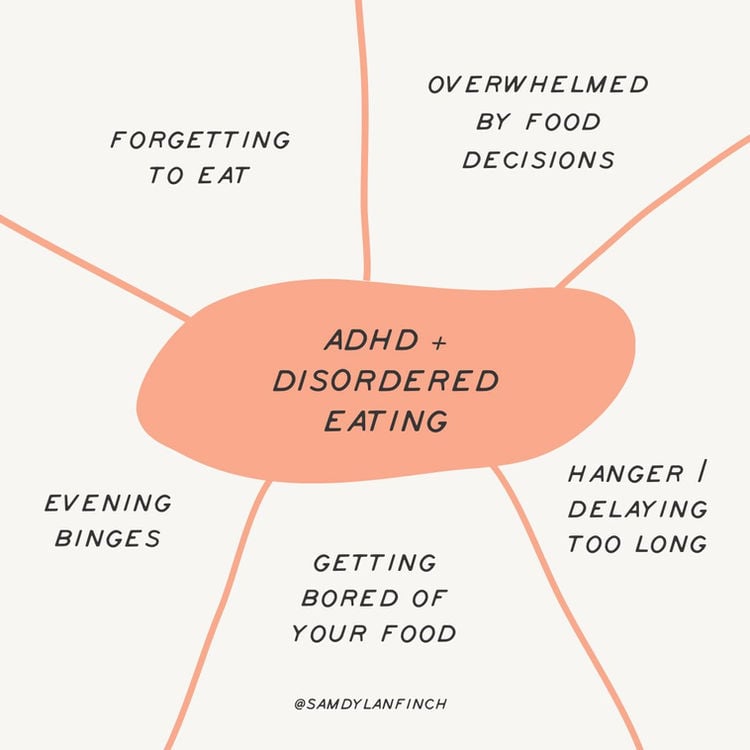

If you’ve never struggled with ADHD, it might be hard to imagine how a so-called “disorder of attention” could lead to an eating disorder. But for those of us living with it, it’s not a stretch to imagine.

ADHD and eating disorders

ADHD can cause eating disorders

My struggles with food began with forgetting to eat.

I could easily get lost in my work, looking up only to realize it was two o’clock in the afternoon and I hadn’t eaten anything yet. Skipping meals felt normal to me. I didn’t realize the damage I was doing to my body in the process. It became especially hard as I entered my mid-twenties when I began taking Adderall for my ADHD, suppressing what little appetite I had left. (This is a common side effect of stimulant medication.)

ADHD can make eating disorders worse

Soon, I was lost in a cycle of “famine and feast.” I’d eat very little during the day, only to have my appetite come roaring back in the evening. With little executive function for meal planning and cooking, I’d reach for whatever was easiest to eat. With time, that meant subsisting off of nutritional shakes during the day and ice cream or cereal at night.

I never imagined that anorexia could look this way. After all, what anorexic eats ice cream for dinner? But I was, and I did.

Worse yet, I’d feel so guilty about the ice cream, I’d spend the next day trying to compensate for my so-called “sugar addiction.” I really thought the ice cream was the problem.

But the real problem? I was under-eating and malnourished, without even realizing it.

The restrict and binge cycle

I didn’t know it at the time, but a lot of people with ADHD struggle with disordered eating, too. And not enough of us are talking about it. The cycle goes something like this:

Restrict

We’re mostly disinterested in food during the day — we might forget to eat, or we find preparing food to be too complicated. So we avoid food altogether, maybe opting for small snacks here and there.

Binge

Come late afternoon or evening, we can no longer avoid food. We’re famished. So we reach for whatever food is easiest to obtain — usually calorie-dense, “sugary” foods, or my personal favorite: takeout.

Continuing the cycle

This makes sense, though. Our blood sugar is crashing, and we have to compensate for the food we didn’t eat during the day… and we need to get our blood sugar back up quickly. Feeling guilty about the “bad” food we ate that evening, many of us vow to eat a more balanced diet from there on.

Many will spend the next day avoiding food again out of guilt, or eating low-calorie foods that we think are good for us… not realizing that what our bodies are asking for is more food, and more calories — not leafy greens and quinoa or whatever else we think we “should” be eating.

Why you don't think you're hungry

Time and time again, I insisted to those around me that I wasn’t hungry. “I just have a low appetite,” I’d say. “I’m basically like a bird!” Human beings are not birds. Our nutritional needs are drastically different.

The real problem is: the less we eat, the more our hunger signals are diminished. This is an adaptive strategy that our brains rely on during times of famine. Rather than bombard us with hunger, when food is scarce — or when our brains think food is scarce — it begins to shut down the signals that tell us we’re hungry to begin with.

The longer we avoid or restrict our food intake, the less likely we are to have reliable hunger signals. Thus, we become convinced we’re “just not hungry” or have a “bad appetite.” The reality is, though, that forgetting to eat or avoiding food due to stress is often what’s causing this decrease in appetite.

You are hungry, even if you don’t realize it. And it’ll take consistent eating to bring those signals back online more consistently.

How to cope with disordered eating caused by ADHD

Becca King, the “ADHD Nutritionist,” wrote in a recent Instagram post, “So how do you break free from the binge/restrict cycle? By eating more consistently throughout the day! Definitely easier said than done, but it is possible.

“Restriction during the day — whether intentional or not — makes it more likely to overeat or binge at night because your body is trying to make up for what it missed during the day,” she continues. “It's your body protecting you, but when you get to the point of feeling ravenous it's hard to eat in a mindful, conscious way.”

And this is exactly what I learned in my own journey with anorexia: consistent eating — every 3 to 4 hours — helped bring my hunger signals back online. I did this with the support of a Health at Every Size dietitian and therapist, but reaching for other tools (like alarms, reminders, calendar events, meal buddies, and more) can be just as helpful.

Final thoughts

It’s been a process — especially in a culture that demonizes foods as good versus bad, healthy versus unhealthy.

But what I learned was that undereating was far worse for my body than any food I could eat, ice cream included.

.jpg)