Neurodiversity is a non-medical term describing natural divergences in how the human brain functions and develops. The term aims to include people whose neurological development doesn't fit the notion of "normal," aka neurotypical.

Neurodivergence acceptance is about focusing on neurodiverse people's strengths instead of pathologizing their limitations.

But - neurodiversity is also a decidedly political concept rooted in the autism movement.

As a concept, neurodiversity draws from both the social model of disability—which argues that a disability can be deepened by societal exclusion—and biological sciences—which see neurodiversity as an integral part of cultural and societal stability - much like how biodiversity is crucial for ecosystem stability.

Interested in learning more about neurodiversity? You came to the right place.

Too long; didn't read

- Neurodiversity is the concept that diversity in human brains exists and that these variations are not something to be cured but to be cherished. The idea is decidedly political and comes from the autism rights movement.

- Many mental health conditions are classified as "neurodivergent." Some examples include autism, ADHD, and dyslexia.

- Certain predispositions for medical conditions can be considered neurodivergent.

Where did the term 'neurodiversity' come from?

Neurodiversity has always been an integral part of human societies. The phrase and concept were developed by Judy Singer in 1998, although she previously didn't get much recognition, only being acknowledged for "coining the phrase."

While the term originated from the autism movement, nowadays, "neurodiversity" is used to describe multiple conditions.

To quote her thesis that first put forth the idea of Neurodiversity:

It feels like cultural appropriation to speak for those whose experiences are further out from the accepted norm than mine, but on the other hand, I'm unwilling to relinquish recognition for my own share in the pain of the oppression.

Singer's thesis "Odd People in: The Birth of Community Amongst People on the Autistic Spectrum. A personal exploration based on neurological diversity" not only lays the groundwork for a modern, accepting, and inclusive understanding of neurological differences but it's also decidedly political in its writing and research method.

She draws from feminist theory, emphasizes the political significance of private matters, questions the "false objectivity" of social science research, and argues that researchers' personal experiences and biases should be considered.

As someone who identifies as autistic, Judy Singer brings a unique perspective to the discussion. Not only is the paper important from a scientific and social perspective, but it's also immensely enjoyable to read.

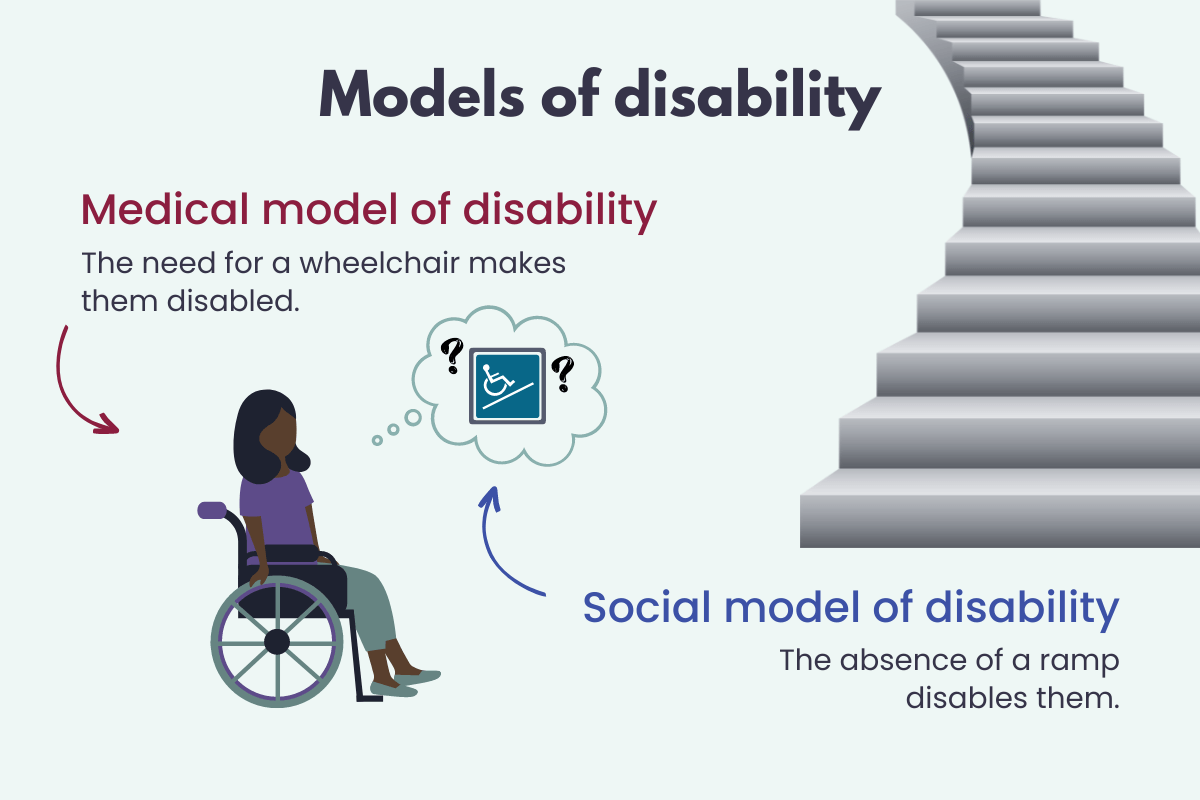

The social model of disability

In contrast to the medical model of disability (which locates the root of disability within an individual's physical body and seeks to "cure" or manage disability through medical interventions,) the social model of disability focuses on society's role in creating inaccessible environments.

The social model of disability differentiates between impairment and disability:

An impairment is a trait of an individual body. A disability is a social product, the result of a society that doesn't take accessibility needs into account.

For example, a wheelchair user in front of a set of stairs is not disabled because they have a wheelchair, but is being disabled by the absence of a ramp.

What does neurodiversity mean to you?

Having - hopefully - given enough credit to the creatrix (creator), let's look at the term's implications and concept.

Self-advocacy

When Judy Singer wrote her thesis, the internet was in its infancy, social struggles on the agenda, and psychoanalysis in decline.

She writes from the perspective of a person on the autism spectrum and is active in internet forums for autistics. For the first time, computers and the internet give autistic people an easy way to connect, as "it mirrors the way their minds work" and circumvents the typical difficulties of social situations.

These self-advocacy groups aimed to stop viewing autism as something to be "cured." This development coincided with the general decline of psychoanalysis, which, in her view, mainly aimed at pathologizing people.

A struggle for acceptance emerged: acceptance of difference, deviance from the "norm," a battle in a neurotypical-dominated society.

Born from the autistic movement, neurodiversity emerged as a social movement critically evaluating society while focusing on quality of life issues and crossing national borders.

A perfect example is the website "Institute for the study of the neurologically typical," which turns the tables and parodies the way neurodivergent people are pathologized and "symptomized" by neurotypical medicine.

A middle ground between disability models

The concept of neurodiversity offers a middle ground between the medical and the social model of disability.

Judy Singer criticizes how the social model of disability focuses too much on purely societal implications of disability. While she also argues that we shouldn't "let the devil have all the best tunes" when she points out that the field of biology and creationism has been left uncontested to conservatives and right-wingers.

She argues - while societal and environmental factors present significant obstacles to the quality of life of neurodivergent people, we shouldn't forget that we're neurologically different from the majority. She reasons this could be a strength—a necessity to cultural development, just like biodiversity is necessary for the environment.

A social principle

While neurodiversity is now an accepted term for inherent differences in humans, it's also a general outline for a better organization of society and relationships:

From each according to [their] ability, to each according to [their] needs.

💭 Philosophical translation? Everyone should contribute what they can to society and receive what they need. Those with more abilities or resources should contribute more, and those with more significant needs should receive more support.

A success story

Today, more people are aware of the general idea of the terms "neurodiverse," "neurodivergent," and "neurotypical." This is a success story in itself.

But the success story of neurodiversity doesn't end there. Neurodevelopmental conditions are becoming more recognized for what they really are:

Our brains are just wired differently; they're not dysfunctional. And society is finally beginning to recognize the value of these different wirings.

What conditions are classified as neurodivergent?

While explaining neurodiversity, I have relied almost entirely upon Judy Singer's original thesis. However, to answer the question of what conditions are neurodivergent, we should expand our view a bit.

In her thesis, Singer mentions only autism, AD[H]D, and the "dys-s" (dyslexia, dyscalculia, etc.). But she also states:

"[The] significance of the ‘autistic spectrum’ lies in its call for an anticipation of a ‘Politics of Neurodiversity.’ The ‘Neurologically Different’ represents a new addition to the familiar political categories of class/gender/race [...]."

Her viewpoint suggests that the concept of the "autistic spectrum" calls for a broader understanding and acceptance of neurological differences, including those traditionally labeled as "disorders" or "mental illnesses."

Examples of neurodiverse conditions

- Autism

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Sensory processing disorder (SPD)

- Dyspraxia

- Dyslexia

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Dyscalculia

- Tourette syndrome

- Dysgraphia

- Synesthesia

Final thoughts: the neurodiversity umbrella

Singer explored the concept of “normal” and its origins, saying that societal expectations of normal behaviors are set and perpetuated by those who fit into the dominant neurological type, or "neurotypicals.”

Autistic individuals have started to recognize themselves as a marginalized neurological minority, subjected to oppression by the neurotypical majority. This represents a significant shift in how autistics perceive themselves and their place in society.

So, who belongs under the umbrella of neurodiversity? Should it be everyone who has ever felt oppressed or unaccommodated in a neurotypical society?

Well, I’d say that seems to be very much in Judy Singer’s spirit.

Source

Judy Singer | Odd People In: The Birth of Community amongst people on the Autistic Spectrum. A personal exploration based on neurological diversity

.png)

.png)