If you’re part of the AAPI (Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders) community, you may remember plenty of things about growing up in the USA, but it probably took you a while to appreciate the clash of cultural differences between Asians and Americans that shaped our conflicting feelings around the topic of mental health.

For example, many Asian cultures view mental health conditions as a “weakness” to be ashamed of. This is in stark contrast compared to the USA. In fact, a 2019 poll concluded that 87% of American adults believe that mental illness isn't shameful.1

This cultural contradiction can cause confusion and frustration for the AAPI community, which only further perpetuates the idea that it’s shameful to talk about conditions such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD — and that it’s even worse to personally struggle with them.

Disclaimer: As a Filipina-American, I respect and understand the nuances between the terms “Asian American” and “Pacific Islander”. To make it easier, I’ll generally refer to our community as “Asian American” or “AAPI”.

Too long; didn’t read

Even though talking about mental health can be hard, the good news is that it’s finally becoming normalized in most of the developed world. There’s been an increased push in the USA to educate Asian American and Pacific Islander communities about mental health, which could significantly reduce the stigma.

You can be a big part of the solution! Be open with your family. Create awareness around the topic. Teach them that it’s okay not to be okay.

It’s not impossible. My mother finally came around to the idea of therapy and medicine after decades of dramatic opposition to it.

See?! There’s hope!

Remember: seeking professional help doesn’t make you weak. And struggling with ADHD, depression, Bipolar disorder, OCD, etc. is nothing to be ashamed of. You have the power to change the future of the AAPI community and save countless lives … just by being open about mental health with your family.

The mental health stigma in Asian cultures

If you grew up believing you were “weak” or “ungrateful” because of your mental health, you’re not alone. When I started struggling with severe depression and anxiety as a teen, I turned to my mom for help. (Fun fact: it was actually undiagnosed ADHD.)

My mother’s response to my struggle with mental health

The way my mom reacted reflected the damaging effects of the mental health stigma in Asian culture. Here are some highlights:

- As a devout Catholic (and typical Filipina mother) she said to “pray harder” and “go to church” and “everything would get better”.

- She reminded me she sacrificed her life in the Philippines to move our family to America. In other words, I should be grateful - regardless of what's going on in my head.

- Her favorite phrase: “Anak*, what do you have to be ‘sad’ about? You should be grateful you have food on the table and a house to live in. You could be on the streets right now.”

- When things got worse, she refused to let me see a therapist or psychiatrist. She said to hide what I was going through so our family wouldn’t know something was “wrong” with me.

Yeah - none of this made me feel better!

*endearing Tagalog term for sons and daughters in the Philippines

It’s time to take this seriously

Trigger warning: mentions hospitalization

Eventually, the severity of my symptoms led to me being hospitalized; doctors determined I was a serious risk to myself and was admitted immediately.

That was the first time my mom took my mental health seriously.

While this is all in the past (I like to joke about it now; because if I don’t laugh, I’ll cry) — I can’t help but wonder what would’ve happened if the stigma didn’t exist. Would I have been supported sooner? What if my mom didn’t discourage me from taking medication or seeing a mental health professional? And why did she protest anyway?

Mental health taboo: the root of the stigma

Cultural values and beliefs

My mother’s reaction isn’t all her fault — it stemmed from generations of ethnic cultural values that are seeded in how the elders of the Asian community typically view mental health. Some of these beliefs and values include:

1. You must put family above all else. When you’re struggling with mental health, it’s seen as a sign that you’re unable to fulfill your familial obligations — which is inherently shameful in many Asian cultures.

2. Be grateful. In immigrant families, it’s almost always the case that the adults sacrificed and struggled so their children could have a better life. Any signs of discontent may be taken as ungratefulness — an insult for what they went through.

3. Your illness is a punishment. According to traditional religious beliefs, adverse mental health symptoms serve as a punishment for “something terrible you must have done in a past life.”

4. You can always pray it away. Religious beliefs also claim that if you would just “have more faith” and “pray harder”, you could “fix” whatever “demons” are in your head.

… Emphasis on the quotation marks.

AAPI mental health statistics

- According to the 2020 census, 24 million people in the USA identify as Asian American or Pacific Islander — 7.3% of the total population.2

- Of this population, 15% reported dealing with one or more mental illnesses within the past year.3

- The National Latina and Asian American Study (NLAAS) found that at least 17.3% of AAPIs will be diagnosed with a psychiatric condition in their lifetime.4

- Despite this, the AAPI community is three times less likely to seek therapy or medical treatment than other racial groups in the U.S.5

Racism due to COVID-19 negatively affects AAPI mental health

It’s also important to note that the rise in anti-Asian sentiment due to COVID-19 is also taking a toll on AAPI mental health. In fact, 1 in 5 Asian Americans reported one or more experiences with discrimination, harassment, and assault in the past two years because of stereotypes associated with COVID-19.6

The model minority myth

Odds are, you’ve heard about several Asian stereotypes throughout your life.

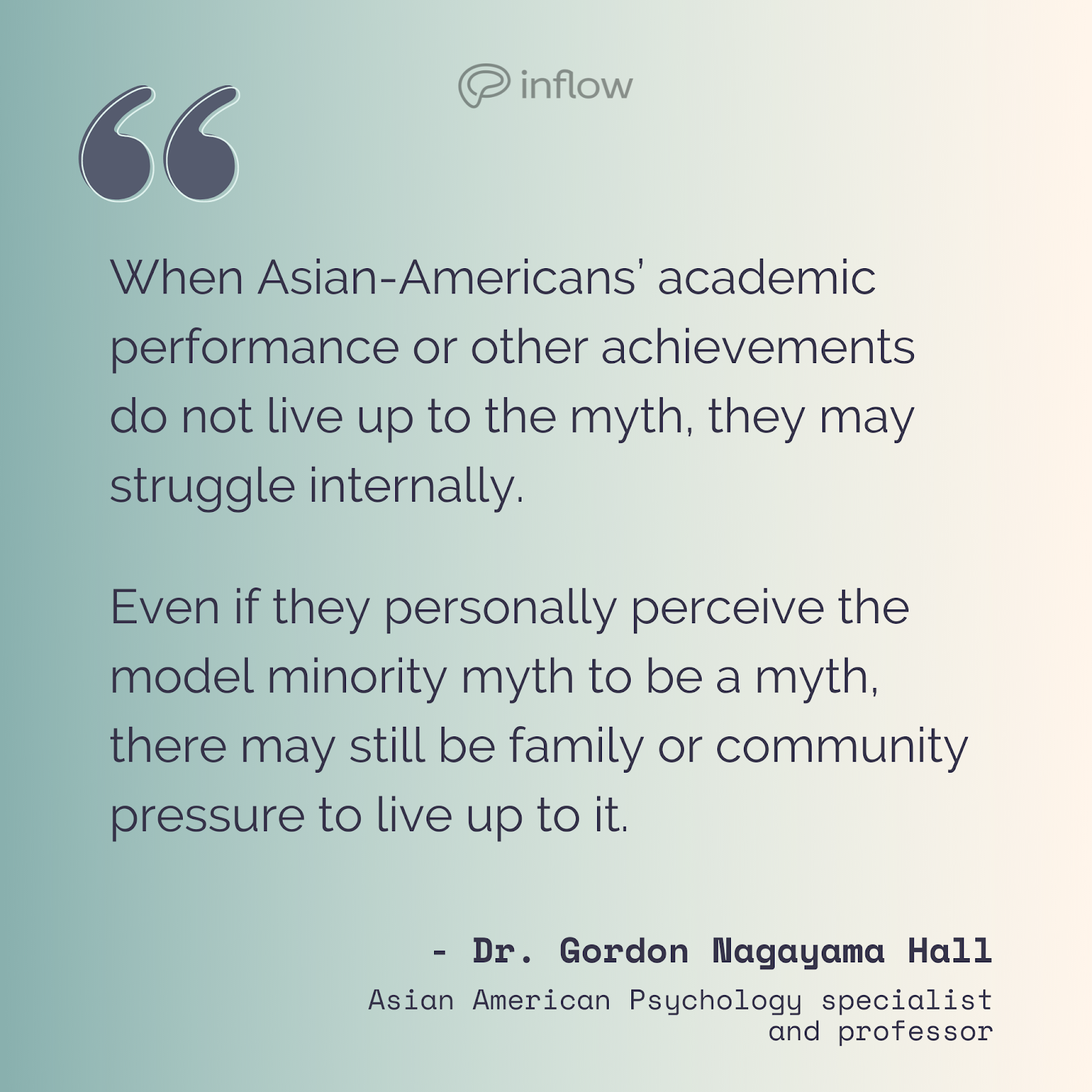

Whether they’re negative or “positive” (i.e. ‘Asians are smart’), stereotypes are still harmful because they dehumanize us and reduce us to our race. These “positive” stereotypes are collectively known as the model minority myth, which places an unfair amount of pressure on Asian Americans to live up to impossible expectations and standards.

And if we can’t live up to them?

Feelings of failure sneak up on us, adding another layer of shame to our already-compromised mental health.

Professor Gordon Nagayama Hall, a specialist in Asian American psychology, further explained the effects of the model minority myth:

Talking to your Asian family about mental health

Everything we’ve discussed so far has been heavy, yes — but it’s shown why it’s so important to overcome the barriers and stigma. Too many Asian Americans struggle, and too many of their stories end in tragedy.

The first step is to normalize mental health discussions and treatment for AAPIs, and you can start by simply opening up conversation with your family about it. But for a lot of us, that can be scary.

Valid concerns for hesitating

If you feel safe enough and decide to talk to your family — great! But it’s also totally normal (and expected) to be anxious about what could go wrong in these conversations, such as:

- Poor reactions

- Refusal to view your perspective

- Arguments and drama

Just start small and keep an open mind. And remember – no matter what their opinion is, your experience is valid!

How to talk about mental health with your Asian family

1. Find resources in your parents’ native language (even if they speak fluent English)

It can be hard for any of us to understand something until it’s translated into our native language. In fact, many Asian and Pacific Islander cultures have no direct translation of “mental illness” or “mental health.” Most health terms are associated with the physical body or spiritual self.

Luckily, there’s been a big push in the USA to translate more resources into such languages.

Where to start:

- National Council on Interpreting in Health Care

- A Safe Haven for Asians and Asian Americans

- Asian American Psychological Association

2. Talk to a mental health professional who specializes in AAPI treatment

There are plenty of professionals across the US who are competent in AAPI treatment or even specialize in that area. Many of them believe that educating your family is an important part of treatment.

Once you find the right fit, they can provide tools for your mental health discussions with your family. You can also bring your parents to an appointment so they can learn straight from the source!

Where to start:

- Asian Health Services Specialty Mental Health Program

- National Asian American Pacific Islander Mental Health Association

- South Asian Mental Health Initiative & Network

3. Set healthy boundaries

Even when you have the best intentions, things don’t always go according to plan. Brainstorm an exit strategy if the situation becomes toxic so you can excuse yourself and table the discussion for later.

4. Put your mental health first

The most important tip of all: take care of yourself! Talking about mental health can be difficult, and if it takes a toll on you, it’s time to practice self-care — exercise, journaling, calling a friend, meditation — anything that helps you cope with stress in the days surrounding your conversation with your family.