ADHD is as old as humankind. ADHD-like conditions were mentioned as far back as ancient Greece, and people have been researching the condition ever since.

Looking back on ADHD's history and advancements can help us continue to learn and maybe even unlearn some false information about it.

Let's dive in to learn the long history and social acceptance of ADHD.

Too long; didn't read

- ADHD trait descriptions reach as far back as ancient Greece.

- What we now know as the condition of ADHD has formed. It underwent a variety of changes in definition and names.

- ADHD was gradually recognized as a condition distinct from other developmental disorders.

A note on historical word use

Today, we know better.

That's why in other articles, we would never talk about neurodivergence as a "mental illness," "ailment," or "abnormality." But we can't judge history by modern standards, and we must accurately reflect the spirit of the times. Thus we choose to use these words.

Ancient and early modern history of ADHD

Today we know that ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition. That means that probably sometime around the time the human brain developed, it also started developing "abnormalities." One of these could have been today's ADHD. So, is it so surprising that "early" humanity started noticing that some people just weren't quite like others?

Ancient Greece: "The obtuse man."

Obtuse, meaning: lacking sharpness or quickness of sensibility or intellect; not clear or precise in thought or expression.1

Charming!

In his book "Characters," the Greek philosopher Theophrastus (381-278 B.C.E.) described a man who'd likely be diagnosed with adult ADHD today with "slowness of mind." His is the oldest known description of ADHD symptoms in western literature.2,3

The Middle Ages

Also sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages, any form of mental illness was viewed as a sign of moral inferiority resulting from sin. So it isn't surprising that life likely wasn't enjoyable during that period of neurodivergent people.

1789: Things brighten up (a little)

In the 1700s, a physician working in asylums called Sir Alexander Crichton published a book about the nature of mental health conditions.

He was the first to introduce the idea that mental health conditions don't stem from a person's failings in life but rather have physiological roots. Today's ADHD, he mentions as "abnormal attention," ranging from little attention on one side to hyper-focus on the other. In his view, this was connected to the "sensibility of the nerves."4

Modern times: En route to ADHD

As time progresses, a more nuanced description of ADHD emerges. As a result, science slowly moves away from the idea of moral deficiency towards a more humanistic approach.

1845: An expression is born

Especially common in German-speaking countries, the expression or allegory "Zappelphilipp" is born out of an illustrated book of children's poems by Heinrich Hoffmann. The standard English translation is "Fidgety Phil."

The book ("Der Struwwelpeter") describes a young boy who constantly rocks in his chair at the dinner table until he falls, dragging the tablecloth and everything down to the ground.

The book was intended as an educational resource, and many parents still read it to their kids in Germany.5

1902: "An abnormal defect of moral control."

In 1902, Sir Frederic Still wrote an observation on children who didn't meet the standard for behavior.

He considered this "defect of moral control" to be primarily intellectual and affected children with mental health conditions. Yet, he also found that this didn't apply to everyone. For example, he noted that certain children required "the immediate gratification of self without regard either to the good of others or to the larger and more remote good of self."

He observed an abnormal degree of passionateness and the uncontrolled expression of emotions. In addition, some children showed "an incapacity for sustained attention."

Most cases still described wouldn't meet ADHD criteria today because he told them as the result of defects in moral control. But, at the same time, his description of ADHD symptoms emphasizes modes of emotional expression which aren't explicitly mentioned in any edition of the DSM.

Many consider Still's writings and Goulstonian Lectures to be the beginning of scientific observation of a condition that would eventually be called ADHD.6

1908: Early brain damage and residual illness effects

In the early 1900s, encephalitis lethargica killed hundreds of thousands of people. Many survivors showed irreversible damage to their physical and psychological health.

Alfred F. Tredgold described residual effects as "hyperactive, distractible, irritable, antisocial, destructive, unruly, and unmanageable in school."

Tredgold also proposed "early brain damage" as a reason for these behaviors.7

The 1930s-1960s: A distinct condition takes shape

In the early 1930s, researchers started describing hyperactivity in children and distinguishing it from previous conditions related to residue illness effects.

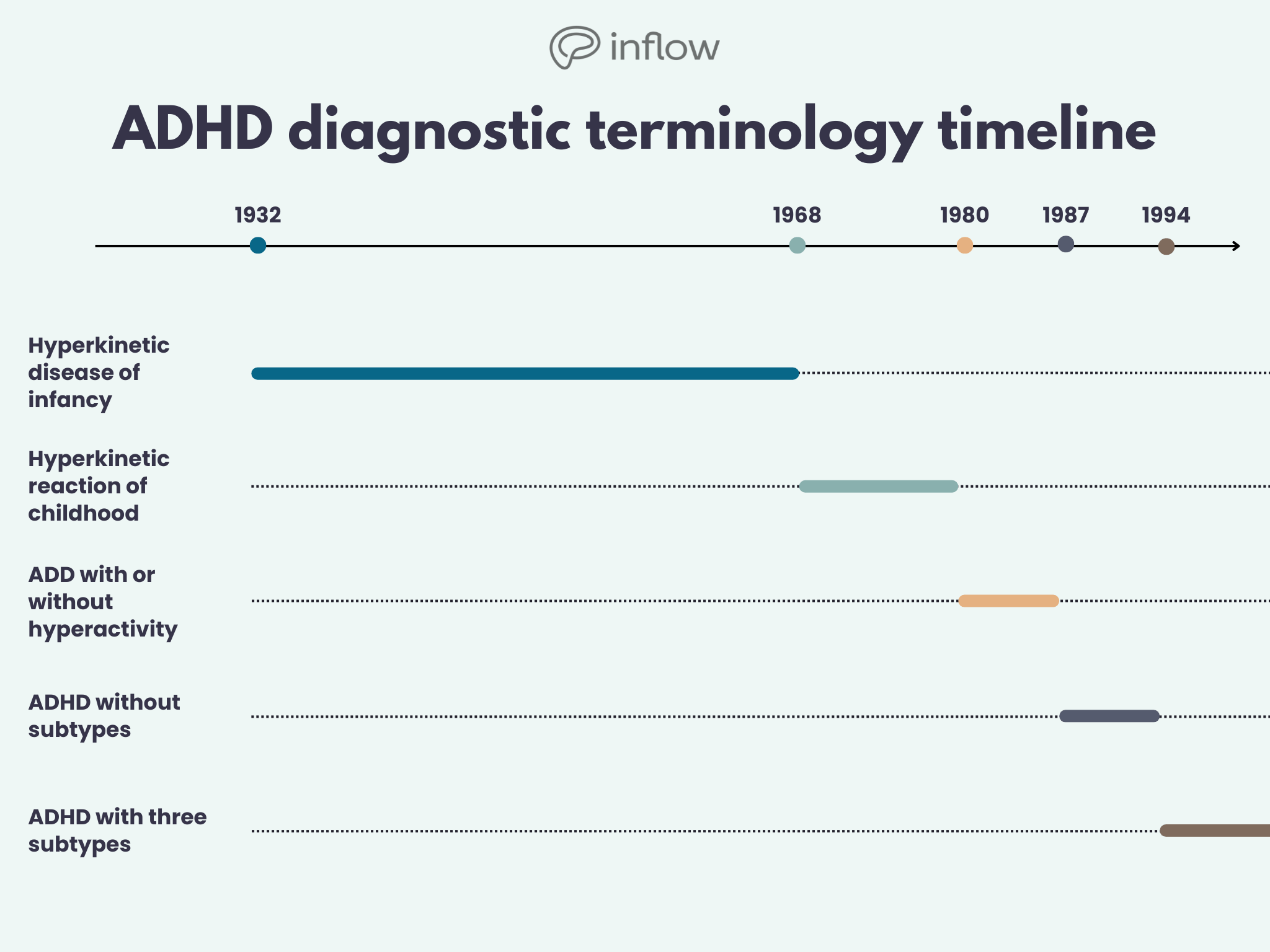

1932: Hyperkinetic disease of infancy

Two German physicians, Franz Kramer and Hans Pollnow, described a condition that contained all the main symptoms of today's ADHD. They noted that these symptoms had previously been observed. Kramer and Pollnow distinguished them from other diseases, such as the aftereffects of encephalitis lethargica.

The hyperkinetic disease of infancy includes the three main ADHD symptoms - hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. There were also two additional DSM criteria: significant impairment in daily life and onset before age seven.

Thus they lay the groundwork for recognizing and treating ADHD in children.8

1936: FDA approves Benzedrine

Benzedrine was initially intended to treat narcolepsy, depression, and chronic fatigue. Its stimulant characteristics made it very popular with the general population, especially among soldiers during WWII.

At the time, the effects and risk of addiction to amphetamines weren't well understood, leading to widespread misuse of the drug.9

1937: Benzedrine studies on school children with various behavior disorders

By chance, the pediatrician Charles Bradley discovered that Benzedrine positively affected children who typically struggled with attention span, motor activity, and impulse control. He subsequently studied the effects of Benzedrine on 30 schoolchildren.

Due to the influence of psychoanalysis, mental conditions weren't considered to have biological causes at the time. Thus, the discoveries of Bradley remained inconsequential for over 20 years.10

1944-1955: Ritalin development and FDA approval

Like Benzedrine, Ritalin was first used to treat narcolepsy and depression. In 1954 it was reported to be a stimulant. It was subsequently used to treat "maladapted children," including some with ADHD, based on the works of Bradley.

The 1950s-1960s: Minimal brain damage and dysfunction

In the 1950s, the notion that hyperkinesis and other behavioral disorders were due to brain damage in early infancy or later childhood was widespread. At some point, almost all children showing signs of hyperactivity were presumed to have minimal brain damage, even if this couldn't be directly demonstrated.

Criticism of this idea caused the need to differentiate further the group labeled "minimally brain damaged." The category of "minimal brain dysfunction" was created to include children with hyperactive, impulsive, and inattentive symptoms with otherwise average intellect.11

ADHD is introduced into the DSM - under a different name

In 1968, ADHD, under the name of "hyperkinetic reaction of childhood" at the time, was introduced into the second edition of the DSM.

1968: Hyperkinetic reaction of childhood

As "minimal brain damage" continued to be criticized as "too generalized," conditions focusing on the specific deficits were named.

Dyslexia, learning disabilities, and language disorders were introduced alongside hyperactivity.

The hyperkinetic reaction of childhood, defined as a condition characterized by hyperactivity, restlessness, distractibility, and short attention span, was introduced into the DSM.12

1970: Common mental health and ADHD myths

On June 29, 1970, the Washington Post published an article: "Omaha pupils given behavior drugs."

The report falsely claimed that 10% of pupils in Omaha were receiving Ritalin. Since then, myths and misconceptions about ADHD have spread and the stigma is still being battled today.13

From "ADD" to "ADHD"

1970s

The emphasis shifted from hyperactivity to attention-deficit.

1980

Official name change in the DSM-III: "attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity"

1987

The DSM-III was revised, and the name changed to ADHD. The subtypes of attention deficit and hyperactivity were combined into a single list of symptoms.

1994

The DSM-IV introduced three distinct subtypes of ADHD and added that ADHD is not exclusive to childhood but can persist into adulthood.14

The 2000s: The fight for public opinion

During the 2000s, while ADHD was firmly established as a disorder, many myths were still circulating. As a result, many physicians and ADHDers started advocating for better treatment, recognition, and acceptance.

In addition, expert statements like the 2002 consensus statement and the 2020 female consensus statement were aimed at destigmatizing and accurately portraying ADHD.